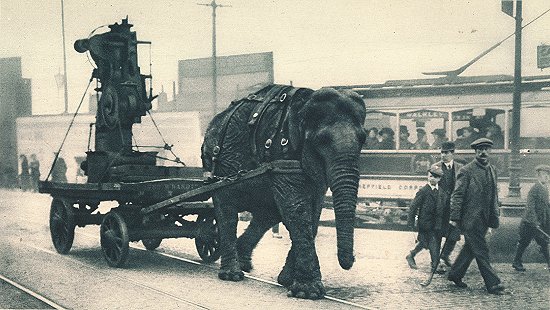

A military elephant in World War I pulls ammunition in Sheffield. Image courtesy Illustrated War News.

Over the years a range of animals have made an invaluable contribution to Australia’s military history. Useful companions and dependable comrades, animals served, suffered, and died alongside the nation’s soldiers.

In the First World War horses, donkeys, camels, mules and even elephants were used to transport soldiers, weapons, ammunition and food. Homing pigeons were employed to convey messages, and dogs to track the enemy and locate injured soldiers. Even the humble European glow worm made a contribution to the war effort; soldiers in trenches would keep a jar of glow worms to read with by night.

Australian soldiers adopted a variety of animals and birds as mascots and pets. They served as morale boosters and provided a familiar and welcome source of comfort and consolation. They included wallabies, kangaroos, rabbits, possums, parrots, cockatoos and kookaburras.

Animals generally endured worse conditions than the soldiers, often exposed to the elements with inadequate shelter. Like their carers, animals were subjected to artillery fire and gas attacks. Special nose plugs for horses were developed to enable them to breathe during a gas attack; gas masks were later developed for both dogs and horses.

It has been estimated that eight million horses and one million dogs died during the First World War.

In November 2004 the Animals in War Memorial was unveiled in London’s Hyde Park to pay tribute to all the animals that served, suffered and died in war. It bears the inscription:

“This monument is dedicated to all the animals that served and died alongside British and allied forces in wars and campaigns throughout time. They had no choice.”

The Australian War Memorial in Canberra also has a monument acknowledging the contribution of animals in war.

Red poppies are an enduring symbol of remembrance to commemorate our war dead. The purple poppy commemorates the contribution and sacrifice of animals in war.

Animals in WWI – a tribute

Companions in the Trenches

War Animals

Walter Farrell of the 2nd Divisional Signals Company with unit mascot Jack, France, 1917. Jack was a better guard than a dog; he attacked any stranger who entered the unit lines. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

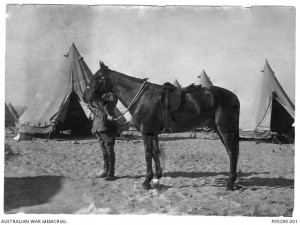

Horses

More than 136,000 Australian horses served in the First World War. Originally from New South Wales, these sturdy, hardy horses became known as ‘Walers’.

In September 1914 Australian Defence Force buyers began to scour the country in search of horses suitable for war service. In October 1914 the Leader published an article outlining the requirements for military horses, and in December the government buyer purchased at least 12 horses from Orange for military purposes. Troops of the Light Horse that departed from Orange in August 1914 provided their own mount.

Horses were issued a service number which was branded on the fore hoof; the unit number was branded on the hind hoof. Each horse was branded on the shoulder with the Government broad arrow (used to identify Defence owned property) and the initials of the purchasing officer.

Horses were primarily used to transport ammunition and supplies to the front, for reconnaissance and for carrying messengers, pulling artillery, ambulances, and supply wagons. They were also used to make cavalry charges.

When peace was declared many Australian light horsemen were shocked to learn that their mount would not be accompanying them home. Lack of shipping, transportation costs and quarantine concerns resulted in 13,000 surplus horses being sold off, transferred to other armies or humanely destroyed. More than 3,000 horses were destroyed.

Major General Sir William Bridges’ horse – “Sandy” – was the only horse who returned to Australia. Following the General’s death at Gallipoli in May 1915 Sandy was sent to Captain Leslie Whitfield, an Australian Army Veterinary Corps officer in Alexandria. Sandy remained in Egypt until he and Whitfield were transferred to France in March 1916.

In October 1917 Minister for Defence, Senator George Pearce, called for Sandy to be returned to Australia. Sandy arrived in Melbourne in November 1918 and was turned out to pasture at the Central Remount Depot at Maribyrnong. In May 1923 Sandy’s increasing blindness and debility prompted the decision to have him put down, “as a humane action”. Sandy’s head and neck were mounted and became part of the Australian War Memorial’s collection.

A memorial to the Australian Light Horse was unveiled in Tamworth in October 2005.

Major General Sir William Throsby Bridges and his mount, Sandy, at Mena, Egypt, in 1915. Sandy was the only Australian horse to return from WWI. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

Dogs

Roff, a German message dog captured by the 13th Battalion near Villers-Bretonneux in May 1918. Roff’s name was changed to Digger; his stuffed and mounted skin is now in the Australian War Memorial’s collection. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

As the network of trenches spread throughout the Western Front during WWI, so did the number of dogs. Both the German and Allied sides employed dogs on the battlefield.

Many different breeds of dog were utilised but the most popular were medium-sized, intelligent and trainable breeds such as Doberman Pinschers and German Shepherds. Smaller breeds such as terriers, were trained to hunt and kill rats in the trenches.

Military dogs fulfilled a variety of roles, depending on their size, intelligence and training.

Sentry dogs were patrolled using a short leash and a firm hand. Sentries were trained to bark or growl when they perceived an unknown or suspect presence in a secure area such as a camp or military base.

Scout dogs were highly trained and possessed a quiet and disciplined nature. They were used on foot patrol, and utilised their keen sense of smell to detect the enemy, often up to a kilometre away. Unlike sentry dogs, scout dogs were trained to be silent; to stiffen their bodies, raise their hackles and point their tail if the enemy was in the vicinity.

Casualty dogs – also called mercy dogs – were trained to locate the wounded on battlefields. Equipped with medical supplies for those soldiers able to tend their own injuries, mercy dogs would remain with severely wounded soldiers, accompanying them as they died.

Messenger dogs proved to be highly reliable in the dangerous job of conveying messages. Running more quickly than a person, particularly over rough terrain, dogs were less visible and less of a target for enemy snipers.

Dogs were also adopted as pets and mascots. “Sergeant Stubby” was adopted as a mascot by the 102nd Infantry, 26th Division of the US Army. Stubby participated in four offensives and 17 battles on the Western Front. He warned of gas attacks, of approaching artillery shells and located wounded soldiers in the field. Stubby became the most decorated dog in military history, and the only one to be promoted to sergeant.

Birds

Homing pigeons have been used as a method of communications in war since the classical era. Pigeons are silent, difficult to intercept, not significantly affected by gas or noise and can be trained to home to mobile lofts.

Around 100,000 pigeons served Britain in the First World War, carrying vital messages across dangerous territory. Despite advances in technology, such as radar, wireless and telephone, message-carrying pigeons continued to play a vital role after WWI.

Secret Service birds were dropped at pre-arranged locations in enemy territory by airmen at night; carried to the ground in special cages with parachute attachments, enabling agents in enemy territory to communicate with headquarters.

On several occasions pigeons successfully brought in messages in from gas affected areas as they were able to fly above the gas.

Homing pigeons had a 95% success rate, prompting the German Army to bring hawks to the front lines to hunt the pigeons down.

Canaries are about fifteen times more sensitive to poisonous gas than people, so were used to detect the presence of poisonous carbon monoxide gas following mine explosions.

Canaries and white mice were used to check the air purity in tunnels; their increased heart-beat would indicate a danger point.

Cats

Cats were a common sight both in the trenches and aboard ships, where they hunted mice and rats. An estimated 500,000 cats were dispatched to the trenches, where they killed vermin and were used to detect gas. Beyond their “official” duties, they were also embraced as mascots and pets by the soldiers and sailors with whom they served.

The feline mascot of the light cruiser HMAS Encounter, peering from the muzzle of a 6 inch gun. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

Dickin Medal

The Dickin Medal was instituted in 1943 by Maria Dickin CBE, the founder of the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA), a British veterinary charity. The medal acknowledges outstanding acts of bravery or devotion to duty displayed by animals serving with the Armed Forces or Civil Defence units in any theatre of war throughout the world. The medal is regarded as the “animals’ Victoria Cross”.

The bronze medallion bears the words “For Gallantry” and “We Also Serve” encircled by a laurel wreath. The green, brown and sky blue stripes symbolise the naval, land and air forces.

The Medal has been awarded 66 times; the recipients comprise 32 pigeons, 29 dogs, three horses and one cat.

An Honorary Dickin Medal was awarded retrospectively to the WWI horse “Warrior” to acknowledge the gallantry and devotion of the millions of animals that served during the First World War.